A road map for building a modern Nolan Ryan

Leigh Montville was one of the few writers to get an up-close look at Nolan Ryan’s offseason routine.

Prior to spring training in 1991, the Sports Illustrated writer traveled to Ryan’s Texas ranch and observed him for a day, curious to see what a legendary capacity for work entailed.

Ryan holds the all-time strikeout record, 5,714 of them, nearly 900 more Ks than second-ranking Randy Johnson. The mark is a testament to his rare stuff, and prodigious volume.

Ryan ranks fifth all-time in total innings, trailing three pitchers with black-and-white photos at Baseball-Reference.com, and another that threw a knuckleball (Phil Niekro) as a primary pitch. Ryan’s volume is even more impressive as he accomplished it as a high-velocity arm. He was not tossing the mid-80s fastballs of the 1920s.

Ryan’s workout began on his driveway on a gray, late winter afternoon. Ryan stretched out by tossing a heavier training implement – a football – to Harry Spilman, a neighbor and former teammate with the Astros, who caught his offseason throws.

Ryan learned the football routine from his pitching coach with the Texas Rangers, Tom House, an iconoclastic pioneer in biomechanics. Ryan was reluctant to adopt the practice at first as he watched the other Rangers throw the heavier ball during pre-game works beginning in 1989. But after studying it and talking to House about the concept, he began throwing a football , too. It turns out working with heavier training implements promotes health through building stronger shoulder- and arm-stabilizing muscles, particularly important in deceleration.

Following the football tosses, Ryan and Stinson began throwing a baseball in his driveway. Easy tosses.

“So, Roger Clemens is getting five million dollars,” Nolan said to Montville, shaking his head. “If Roger’s worth five million, what’s Wade Boggs going to be worth?”

Perhaps he arrived too early. But had he arrived later, he might not have been permitted to log the work, the innings, and accumulate the numbers he did.

After those light tosses, they moved to Ryan’s makeshift field in a plot of open pasture.

Wrote Montville: “Nolan put on his blue Rangers cleats to throw …. Hard tosses. The workout began a little before five o’clock, and now the time is a little after six. The light is almost gone. The dogs have lost interest, running into the woods in what would be a dead center field. Nolan says, ‘They’re probably looking for yesterday’s game ball.’ A pitcher’s grim joke. …Nolan says this is the kind of light he wouldn’t mind having for all baseball games all of the time. He asks Harry if there is enough light for one more pitch. Harry says that there is.”

Ryan began engaging in these workouts with Harry beginning in the middle of January. He continued them until he reported for spring training. He had a throwing plan.

This was in addition to the running- and weight-lifting routines he was known for at a time when such strength work was not common among pitchers. Three times in the week he did three sets of 12 bench presses with a 150-pound barbell, ran wind sprints for 15 minutes and a stationary bike for a half hour.

The routine perhaps explained how on the day Montville observed Ryan, the Hall of Famer was entering his 26th year in professional baseball, selected as a 12th-round pick by the Mets in the first amateur draft in 1965.

Let’s return now to the present day. I begin with that color of Ryan preparing for a season some 35 years ago because a few of us at Driveline were interested in recreating Ryan’s workload. What would building a throwing program for such volume look like? Is it even possible to build up an arm like that today?

Disclaimer: We are not suggesting every pitcher should work toward creating an extreme workload, rather, this an exercise to see what is possible within our data-based constraints.

Ryan was no doubt a freak athlete, a physical marvel. Legend has it that he once hit 108 mph. While he was 6-2, modest by today’s height, he could easily dunk a basketball in high school. He had God-given gifts but his capacity for work was learned. He built himself into a remarkable workhorse.

What can we learn from a player who not that long ago, in 1991, was a volume machine who could still reach 96 mph and toss no-hitters at age 44?

What would it look like to build a greater capacity for volume in today’s game? What would a Ryan-like throwing plan entail? And could it be done within the constraints of workload monitoring?

We were curious to experiment, so pro pitcher and Driveline researcher Josh Hejka, Driveline’s Max Engelbrekt, and myself went to work doing just that in this, the first of an occasional series at Driveline on pitching workloads.

One of the issues with monitoring workload and understanding how to build it is that it’s been difficult to measure the total volume of throws.

The only widespread measure we have had in the modern era – until recently – are pitch counts, which fail to account for every throw an athlete makes: the bullpens, the long toss, etc.

That changed with our PULSE technology.

For the first time, the force of every throw a pitcher makes can be measured and recorded. We can even simulate the workloads of pitchers who are unable or unwilling to use the wearable tech.

PULSE allows us to measure the force of each throw, resulting in a metric called workload units. There’s more intensity tied to a game-day pitch than during catch play, or a bullpen session – and now we can quantify the difference. If we can measure the stress of an entire

day’s worth of work, we can better understand the total stress of pitching and how to better build up pitchers and keep them healthy.

To begin, what constitutes a Ryan-like workload?

We know Ryan threw at least 140 pitches in a start on 10 occasions between 1988-93, the final six years of his career, and the first six years in which MLB pitch count data is available. Those 10 outings represented the sixth-most such games during that span. He threw a max of 164 pitches on Sept. 12, 1989.

The 155-pitch workload, what Ryan was capable of, is equal to 64 workload units. A workload total for a day includes estimated pre-game and in-game work. (One inning, a shade under 17 pitches, is equal to 4.8 workload units.)

A 100-pitch workload, essentially the standard maximum for a pitcher today, is equal to 48 workload units, which, again, also includes pregame work.

So, to become Ryan-like, the challenge is building from a single-day maximum of 48 to 64 workload units.

What does building such volume look like? And can it be done safely?

Hejka is unusually positioned to research this question as he is a professional pitcher, employs PULSE consistently to build and manage workload, and he is also a computer scientist.

He believes increasing volume can be accomplished.

“The analogy I always use is to think about running a marathon,” Hejka said. “If you ask a Joe Schmo off the couch to go run a marathon he’s going to be struggling, and he probably will get hurt or have a really bad time. … If you have someone training for their first, and they go run a marathon, they’ll probably complete the marathon, but they’re just going to barely limp over the finish line. They’re going to be beat up the next day. They’re not going to feel great. But if you have a guy who’s built up to, like, run ironman triathlons, ultra marathons and stuff like that, that guy can run a marathon and he’ll be able to bounce back much quicker than the other guys.

“The total stress, the absolute stress, is the same on all three of those people. But the relative stress is much lower for the ultra-marathoner because he’s prepared for more. So, I think that’s kind of like what we want with our starters and our relievers. We don’t want them to be prepared just for what they have to handle. We want them to be prepared for more than what they have to handle.”

Ryan was likely very over-prepared.

But an impediment is pro baseball is now often conditioned to fear elevated pitch counts, a fear of throwing more.

The idea is that every throw contains a small amount of risk. The fewer the throws, the less chance for an injury. But to build volume, a pitcher must build chronic workload – they must throw a lot.

How much throwing, how to build a throwing program, is key in allowing an athlete to withstand the rigors of a full season. Today we have more tools and data to help create a roadmap.

Let’s quickly introduce a key measure that will guide us: acute-chronic workload ratio (ACWR).

It’s a metric that compares an athlete’s training load over a short period (acute), a week for a pitcher, to their workload over a longer period: the previous 28 days (chronic). The concept of ACWR began outside of baseball, and research extends to a number of sports, too. But there is carryover in principles between different athletic disciplines.

To increase an athlete’s workload, we must elevate their acute workload to be greater than their rolling, chronic workload (ACWR of greater than one) – but we don’t want to increase that workload too quickly as it could lead to injury or performance decline.

While there’s no single metric number that can safely prevent or predict injury, studies have found there is greater risk for a pitcher to sustain an upper-body injury when their ACWR is greater than 1.3 – meaning their short-term workload is 30% greater than their chronic. The optimal ratio for increasing workloads while keeping injury risk minimal is similar in studies of soccer and rugby players, too.

So, to try and build safely toward a massive workload, and to be rooted in objective measures and guardrails, we are constraining ourselves. We are attempting to build a Ryan-like roadmap for our hypothetical pitcher in which his ACWR does not exceed 1.2, meaning his acute workload that does not exceed a level 20% greater than his longer-term workload.

This is where the data and tracking from PULSE is so important for coaches and players, Engelbrekt said.

“Can you confidently send somebody out to throw? Well, if you know that they’re built up, then you can feel much better about it?” Engelbrekt said. “So, we can show if you throw this much, you’re only to this range. It doesn’t guarantee anything, but it does show you’re within your normal range because your chronic workload is so high.”

So, if we are going to build the next Nolan Ryan safely what does that look like in terms of creating a throwing program?

Hejka created several different simulated throwing plans to evaluate.

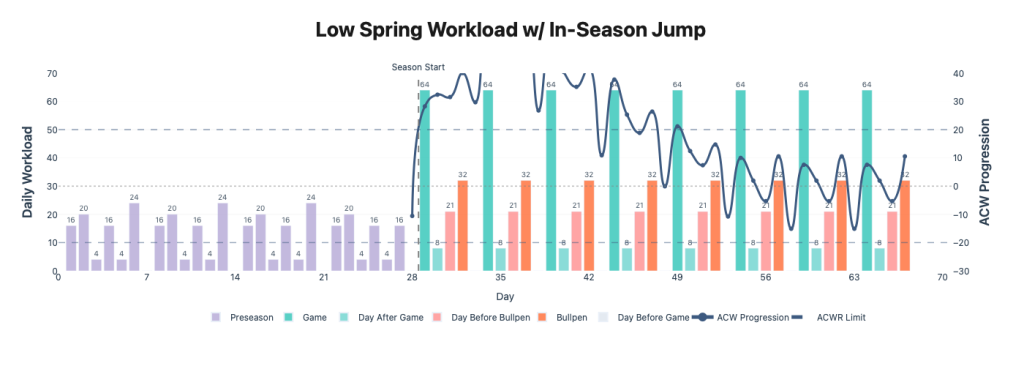

Option No. 1: Jumping from a low pre-season workload immediately into a Ryan-like, full-season workload.

To summarize: this is a bad idea.

“Jumping from a low pre-season workload immediately into full-season workloads is a disaster,” Hejka noted.

Jumping from workload units in the teens late in the spring immediately to a Ryan-level workload immediately places incredible stress on arms.

With such a plan, the pitcher’s ACWR jumps well above the +20% level.

In fact, it jumps off the chart.

And it is in the spring and early season when an outsized number of pitching injuries occur in pro baseball, perhaps in large part because pitchers’ ACWR ratios spike to exceed safe thresholds as pitchers build enough chronic workload – and then throw too much as the season begins.

But what about a more gradual buildup of such a workload in the season?

In this example, the pitcher again goes through a low-volume spring and then jumps to about a 100-pitch level to begin the season before building towards a Ryan-like level in season.

In this example, we again exceed our redline. There’s again a short-term workload spike greater than our 20% target. There is just not enough chronic workload if we begin only building significant workload in-season.

In each of the first two examples we start with 16 workload units 28 days before the season and never have a one-day workload above 24 in the preseason. That’s not enough throwing volume to build up the chronic workload necessary to withstand a massive workload.

What if our simulated pitcher gradually ramps up his spring workload? What does that look like?

The problem, again, is beginning from a low base.

To build a Ryan-like workload we need to ramp up the spring workload – and enter the spring with greater capacity for volume.

So, what would spiking that spring volume do for a Ryan roadmap? What if our pitcher reaches 40 workload units, or 70 pitches thrown in multiple spring training starts? That’s a level we don’t see from starters until late in the spring today.

While this approach marks an improvement, there’s still a potentially adverse 20% jump during a period early in the season. Even dramatically ramping spring workload does not allow us to safely try and replicate Ryan.

Let’s look behind one final door: building a heavier workload in the spring and then combining it with an in-season ramp to build a 64-unit capacity

And it is with this simulation a roadmap to building a Ryan-like workload becomes plausible within our ACWR constraint.

To get there, we doubled the spring training compared to the first three examples, and also continued the ramp up early in the season.

Our hypothetical pitcher reaches 46 workload units in an exhibition start two weeks before the season, which, again, is equivalent to throwing 70 pitches in a game. There is also more throwing in bullpens and during the days after outings. The ramp then continues early in the regular season, as we continue to build a greater chronic workload.

Said Hejka: “A high pre-season workload followed by a gentle progression smooths out the ACWR the best.”

While we cannot get to the 64-workload unit goal on Day 1 of the regular season, interestingly, Ryan built up in a similar manner.

He threw a lot in the offseason as Montville observed, and also built volume in spring training.

For instance, during his final spring start of 1991, he threw 111 pitches over five innings against the University of Texas.

He then continued to build up his workload throughout the season.

During Ryan’s 1972-1980 peak, when he averaged 268 innings and 290 strikeouts a year, his early-season workloads were slightly less than his later season workloads.

He averaged 7.3 innings per start in April during that nine-year span, 7.3 innings per start in May, then 7.5 in July, 7.6 in August, and peaking at 7.7 in September/October.

He continued to build capacity, chronic workload throughout the season.

There is a school of thought pitchers should be throwing more. Much more. And Ryan is an exemplar of that.

Three months after Montville stopped by his ranch, Ryan threw his seventh career no-hitter – his final one – at age 44.

He topped out at 96 mph on the stadium radar on May 1, 1991. His 122nd and final pitch of the day traveled 93 mph to strikeout Roberto Alomar, his 16th strikeout of the game. The Arlington Stadium crowd of 33,439 erupted.

What did he do after that start? The oldest pitcher ever to throw a no-hitter went back to work. The following morning at 7:30 a.m., after 4 ½ hours of sleep, he was in the Arlington Stadium weight room.

Wrote the L.A. Times staff writer Danny Robbins on May 3, 1991: “An extra hour or two of sleep, the morning television shows, even the congratulatory phone calls–they would all have to wait.

‘My life revolves around my workout routine right now,’ the Texas Ranger right-hander said at a news conference later in the day, offering about as good an explanation as any for how, at 44, he had held the Toronto Blue Jays hitless the previous night.’”

While there are few Ryans in baseball history, there is an opportunity for many pitchers to be guided by data to build smarter and safer throwing programs. We don’t want arms to just be prepared, we want them to be over-prepared.

The post Is It Possible To Build Another Nolan Ryan? We Give It A Try. appeared first on Driveline Baseball.